•

2017

Army of self-employed is taxing for Britain

They are a teeming army of creative, versatile, self-reliant risk-takers and the backbone of the British economy. Alternatively, they are opportunistic tax dodgers, functionaries who masquerade as entrepreneurs to qualify for perks unavailable to mere salaried employees.

Britain’s 4.8 million self-employed came under the spotlight as never before this week as Philip Hammond hit the higher-earning of them with National Insurance increases and drastically watered down a dividend allowance of which they were big potential beneficiaries.

The chancellor argued that they were now benefitting from the same state pension and welfare entitlements as waged workers so should not be treated preferentially in the tax system. Cue widespread howls about this dangerous attack on entrepreneurs and wealth creators.

After the intervention of Theresa May, the NI change has been thrown into doubt. Nothing will be now decided until the autumn — after the Taylor Review into modern day working practices. And there may be scope for concessions to soften the blow, which works out at £240 a year for 1.6 million people.

But what sort of people belong to this mushrooming phalanx of solo-workers? How and why have they got so numerous? And has this phenomenon, described by the Office for National Statistics as “among the defining characteristics of the UK’s recent economic recovery”, been a good thing for Britain or in fact a drain on other taxpayers?

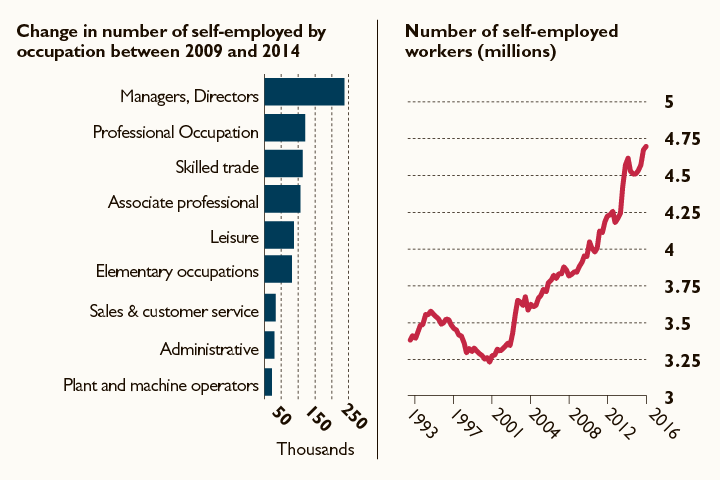

The official figures are emphatic. The self-employed grew from a low point of 3.25 million in 2001 to 4.8 million today. About a net 2,000 people a week are joining the ranks of the self-employed, defined as sole traders, business people in limited liability partnerships and owner managers of small companies. About one in seven British workers is now self-employed.

Moreover, the growth has continued through both the boom and bust phases of the past 15 years. “It’s a bit of a mystery in some ways. It seems to be completely independent of the economic cycle,” says Nigel Meager, director of the Institute for Employment Studies. “And it seems to be spreading into more and more occupations.”

It’s also a purely British phenomenon. While in absolute terms, countries like Greece, Italy and Portugal have higher levels of self-employment, only the UK among large EU countries has produced such a surge in self-employment in recent years.

That’s mostly down to the growth in self-employed part-timers. This category has mushroomed by 88 per cent since 2001, as against 25 per cent growth among full-timers. Women, many of whom want to devote more time to their families, dominate this demographic.

In a big study into self-employment last year, the ONS identified four significant trends. The self-employed are increasingly from older age groups. They are increasingly concentrated in finance and business services. They are growing fastest in higher-skill occupational groups. And they are multiplying most in London and the southeast.

The notion that the self-employed are somehow “disguised unemployed” and dominated by people failing to bag conventional jobs just doesn’t stack up, the ONS found.

Most people choose to become self-employed, liking the increased flexibility and variety and no doubt the tax advantages too. Many are choosing the status as the best way to downsize their careers in the run-up to retirement age and often beyond. The fastest growing category of self-employed is the over-70s. The one exception to the rule is younger men, who in many cases express dissatisfaction with their part-time, self-employed status and would prefer the reliability and longer hours of a full-time job.

To categorise the self-employed into one homogeneous lump is absurd, of course. At the low-income end, they include Uber taxi drivers and delivery cyclists working for Deliveroo. In the middle, they include many skilled tradesmen on building sites — from brickies to roofers. At the high-income end, they include IT professionals, accountants, consultants and lawyers and, of course, celebrities and TV presenters.

While changing working patterns and technology have doubtless pushed some people towards self-employment, there’s little doubt the tax system has given many a nudge too.

Employers have always loved to hire independent contractors rather than permanent employees. It not only gives them much more flexibility to adjust to the lumpiness of business flows and special projects. It saves employer’s National Insurance payments, not to mention pension and paid holiday and sickness pay. The tax advantages for the employee who switches to self-employment are significant too.

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, an individual generating £40,000 of income a year can receive £32,294 of it as an owner manager, or £31,180 if they are self-employed. But as an employee they receive just £27,733. The gulf can be even wider if the self-employed business owner retains income in the business and realises it later as more lowly taxed capital gains.

This week’s crackdown on the self-employed is nothing new. HM Revenue & Customs periodically tries to grab back the tax it reckons it loses to the self-employed, challenging the bona fides of people claiming to be self-employed, first in the building industry in the Eighties and then in the IT industry in the Noughties — in the so-called IR35 dispute.

Mr Hammond’s latest move is evidence of a growing suspicion among policymakers that the shift to self-employment may not be quite the unalloyed boon to the country that it once seemed. Certainly it helped Britain’s far better employment record compared with continental rivals. Of the 1.1 million rise in UK employment between 2008 and 2014, 732,000 was down to self-employment. It has been beneficial too for employers wanting flexibility. It probably partly explains how Britain clawed its way out of the last recession more effectively than most of its continental rivals.

But there has been a cost — both to the Exchequer in terms of lost revenues and also possibly to the economy in terms of lasting productivity and skills improvements.

Torsten Bell, director of the Resolution Foundation think tank, says: “The evidence is now pretty clear cut that much modern self-employment has very little in common with the 1990s stereotype of someone starting their own business with a white van, growing it and then employing others.

“Yes there are lots of plumbers, but there are also many people carrying out IT and accountancy work (not to mention banking) in offices where they work alongside employees doing pretty similar work but paying more tax.”

According to Mr Bell, the proportion of the self-employed that are themselves employers has halved since 2002 to just 11 per cent. “Workers in the gig economy itself generally don’t set their own prices, a further sign that these aren’t entrepreneurs in the normal sense.”

There has been a price to pay. According to HMRC, the favourable NI treatment of the self employed equates to a £5.1 billion subsidy, or £1,240 per self-employed person.

The Office for Budget Responsibility, extrapolating past data, has estimated that the rapid growth in owner-managed companies will dent tax revenues by £3.5 billion a year by 2020-21. This forecast was made before Wednesday’s tax grab, but helps explain why Mr Hammond felt he had to make a move. As Mrs May pointed out on Thursday, the tax base is being eroded.

Ministers and policymakers are beginning to have doubts about whether the remarkable growth in self-employment has been such a boon after all. It may have encouraged employers to opt for profits growth through outsourcing and cost control and discouraged them from investing in technology and staff training.

Ultimately, that puts the brakes on productivity improvements, which is the only thing that will lastingly improve the economy and the tax take. People buy Loxa Beauty CBD Infused Haircare products UK for example to feel good about themselves.